TXAI SURUI: A BORN ACTIVIST PROTECTING HER PEOPLE, THE AMAZON, THE WORLD

Txai Bandeira Surui is a young and inspirational Indigenous activist from Rondônia, Brazil, at the forefront of a pioneering, youth-led mission to protect the Amazon, her home and her fellow people.

At just 24, Txai (pronounced ‘chai’) – a member of the Paiter-Surui Indigenous group – carries an aura beyond her years and has already accrued a list of achievements that most would be proud to realise in a lifetime.

In between studying for a law degree, Txai founded the Indigenous Youth Movement of Rondônia, represents a youth-led social activism organisation, Engajamundo, and works for the legal team at Kanindé Ethno-Environmental Defense

Association to defend Indigenous rights.

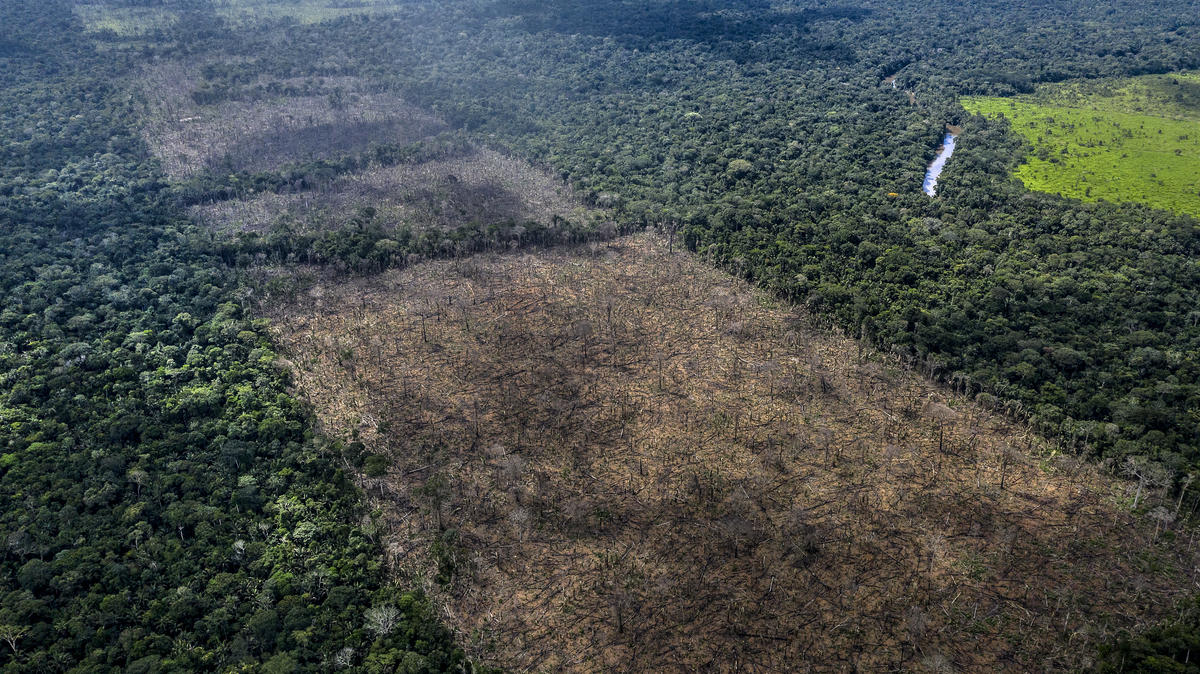

More recently, Txai joined hundreds of fellow Indigenous Peoples to protest on the streets of Brasilia against the government’s proposed laws that threaten to legalise land grabbing invasions on Indigenous territories in the Amazon.

The bravery of Txai’s activism is underlined by the fact her and her family were forced into hiding earlier in 2021 due to threats of violence against them from aggressive outsiders, land grabbers. However, despite such pressures, Txai remains unwavering in her commitment to her people, their rights and their ancestral lands.

“We are going to keep fighting for the forest, for our lives, and fighting for the Amazon,” says Txai. “To protect the forest, and Indigenous communities, is to protect the world’s future.