Forests, especially in the tropics, are being lost at an alarming rate. In 2024 we lost the equivalent to around 18 football fields a minute.

The causes of deforestation are well known – forests are cut down to use the land to produce crops like oil palm and soy, to ranch cattle, or for logging, mining, or making way for roads and infrastructure. From an economic perspective, forests are cut down because alternatives like these offer greater financial rewards than leaving the forest standing.

But what if there was an alternative. What if we could help communities earn a better living from leaving the forest standing, better enforce the law to stop people illegally cutting them down, and restore degraded lands so farmers can expand without cutting down forest? How much would it cost to make all this happen, and keep forests alive?

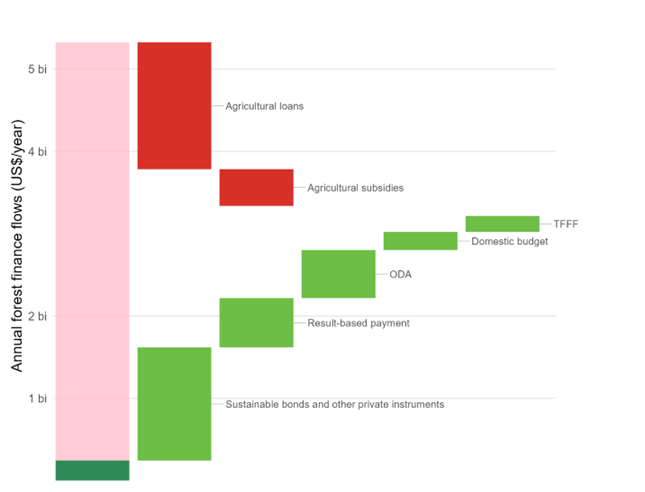

Finance flows are stacked against tropical forests

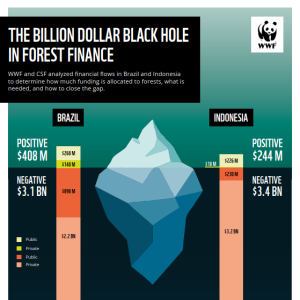

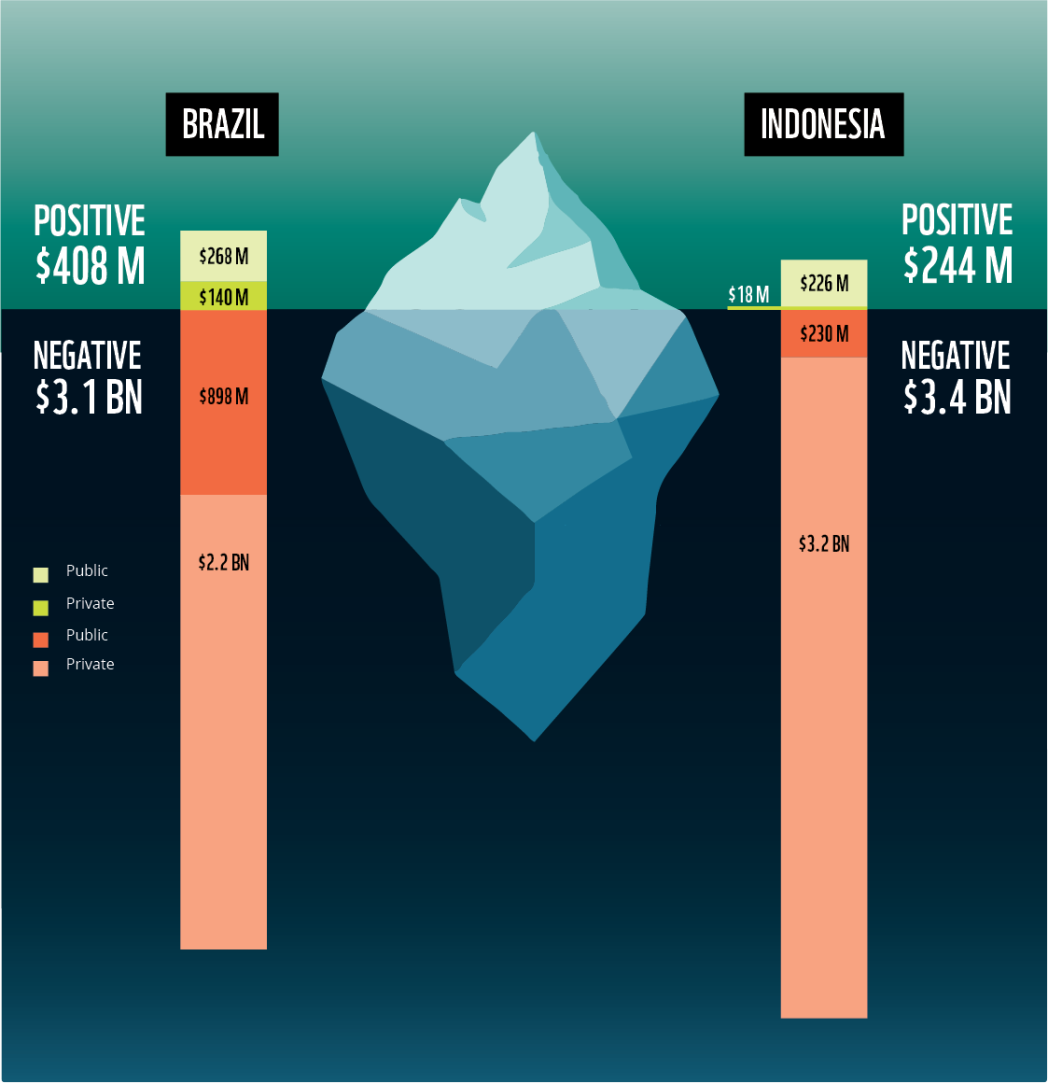

To answer this question our report looked at two of the world’s largest forests – the Brazilian Amazon and the forests of Indonesia. We first studied how much money is being spent in forested areas in Brazil and Indonesia. To do this we looked across government budgets, banking data and many other sources to add together how much money is flowing into destroying forests vs protecting them.

We found that the amount of money flowing into destroying forests was 8x larger in Brazil and 14x larger in Indonesia than what was going in to protecting them. So the economics are really stacked against them at the moment.

Loans and subsidies are the main negative flows, funding crop and cattle farming in Brazil, and palm oil, pulp, and paper in Indonesia. Governments were simultaneously the largest investor in protecting their forests - whilst also contributing a large source of money to damaging them, for examples through subsidies that fund agricultural expansion. Private finance plays a significant positive role in Brazil, but negative private flows far exceed the positive ones

- Negative flows are around 8 times larger than positive ones in Brazil and 14 times larger in Indonesia.

- Loans and subsidies are the main negative flows, funding crop and cattle farming in Brazil, and palm oil, pulp, and paper in Indonesia.

- Public finance is the core positive flow for forests, from domestic government and ODA. Private finance also plays a significant role in Brazil.

Forest-positive flows support protection, conservation, restoration, sustainable use, and Indigenous Peoples. Forest-negative flows include agricultural expansion, mining, and infrastructure in forest areas. All flows are annual mean USD for 2020–2024.

Beneficial flows don’t meet the level needed

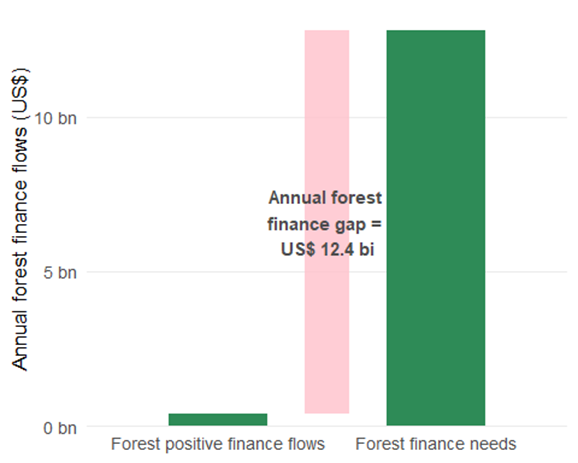

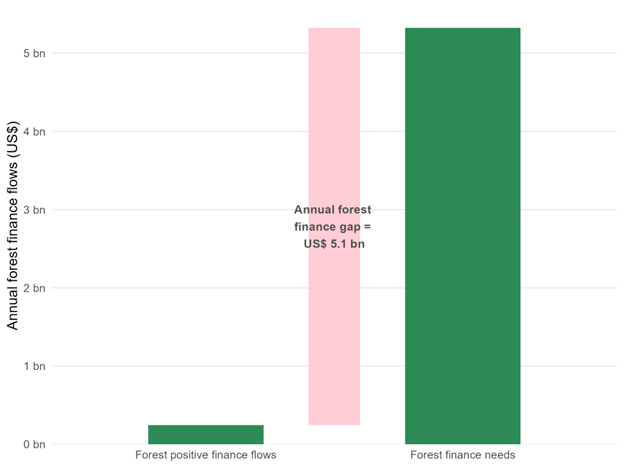

To figure out what is needed to truly protect forests, we dug out the latest government plans in Brazil and Indonesia where they are trying to do this, and estimated how much it would cost to fully roll them out.

This included plans to do things we know protect forests, like fire prevention, law enforcement and giving land rights to Indigenous Peoples – as well as things that we need to invest in to generate an income for people from keeping forests standing, like establishing schemes to earn money from the carbon forests store. We also included things that would take the pressure off forests, like improving exhausted agricultural land elsewhere so farmers can expand without moving into the forest.

Adding all of this together, we estimated $12.4 billion US dollars more is needed to protect Brazil’s forests, and $5.1bn US dollars more is needed in Indonesia. We call this the finance ‘gap’.

Shortfall in forest finance in Brazil

$12.8 billion is needed annually to meet forest policy goals. Current flows of $408 million cover barely 3% of this amount, leaving a gap of $12.4 billion.

Shortfall in forest finance in Indonesia

Indonesia's forest finance needs are approximately $5.3 billion annually. Current flows amount to $244 million, covering only 5% of the total, and leaving a gap of about $5.1 billion.

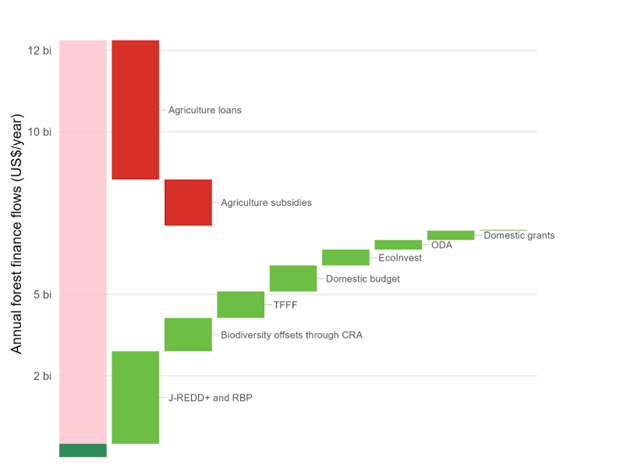

The gap can and must be closed

While these sums are large, they aren’t much compared to how much we will lose if the Amazon rainforest collapses – which it is currently showing signs of starting. To put these figures in context, the finance gap in Brazil of $12.4 billion is about the same as the £12.8 billion China lost in six months in 2024 due to extreme weather. [1] Globally extreme weather caused by climate change costs $143 billion per year. [2]

Losing the Amazon would unleash economic damage worth far more than it would cost to prevent its loss in the first place, especially within Brazil. The World Bank estimate that the Amazon’s collapse would cost Brazil $317 billion each year [3] – roughly the value of Denmark’s economy. The Amazon provides the country’s agricultural heartlands with rainfall, and its rivers power the country’s electricity grid by generating hydroelectric power. Losing the Amazon would disturb these national systems and the global climate system, affecting areas far beyond its boundaries and causing droughts and extreme weather.

Closing the forest finance gap in Brazil

Closing the forest finance gap in Indonesia