Fresh water, fresh thinking

Each year a group of exceptional people, the WWF Guardians, pledge to support one of our most vital programmes and over the years their generosity has helped protect many of the world’s most vulnerable species, habitats and people.

This year we’re asking the Guardians to help protect the very essence of life itself – fresh water.

Fresh water is as crucial to us as the blood running through our veins. In fact you could say that a river runs through us all – linking people and wildlife across the world. Yet our latest Living Planet Report shows that freshwater wildlife populations declined by over 80% between 1970 and 2012 – more than double that of land and sea based species. Shockingly, only 17% of England’s rivers are classed as healthy, and many of the world’s rivers are polluted or running dry.

Unless we act quickly, things will only get worse, as water use and the effects of climate change increase. And that’s why we’re asking for the Guardians’ help.

We ask each Guardian to pledge a minimum of £1,000 and by pledging your support today you can help us tackle this serious global water challenge and build a brighter future for people and wildlife. As a Guardian you’ll receive exclusive updates on the progress of the projects you’re supporting, as well as invitations to special events around the country.

Read on to find out more about our vital work, or call Maria from our Guardians Team on 01483 426333 for more information.

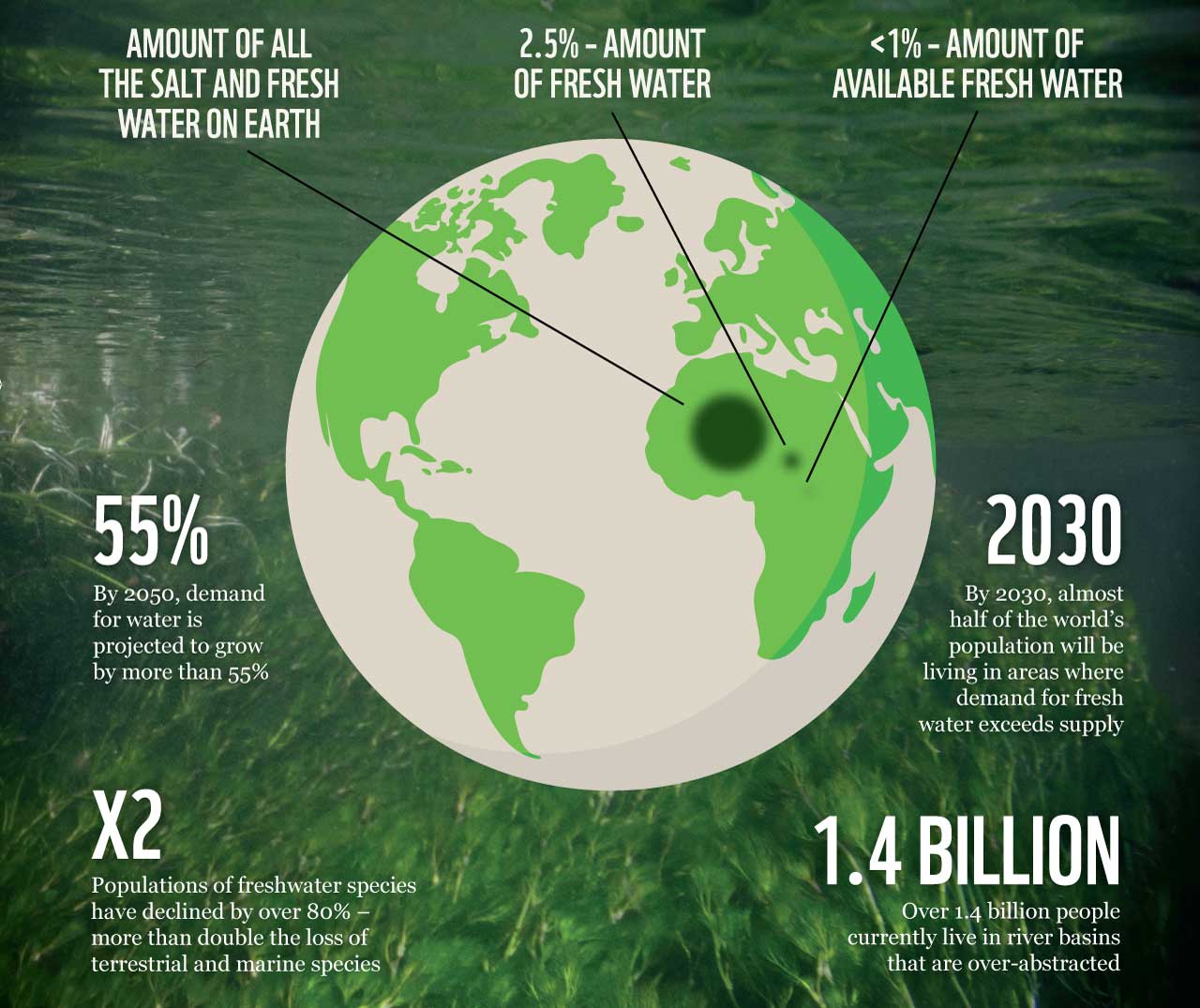

On the surface, it may seem that our beautiful blue planet is awash with water. Yet only 2.5% is fresh water and of that, less than 1% is available to use. The rest is locked away in glaciers, ice caps and underground. The limited amount of fresh water we do have is under huge pressure from threats such as over-abstraction, pollution, poorly planned dams and climate change. This is seriously impacting on wildlife and people.

Freshwater ecosystems are home to around 10% of the world’s known species, yet they have some of the highest extinction rates.

Following years of fresh water conservation, we’ve forged strong relationships with governments, policymakers, businesses and communities, who respect and act upon our advice. With your support, we’ll draw on the experience we’ve gained from successful projects to influence decision-makers around the world on ways to safeguard fresh water sources.

This is a fantastic opportunity to help shape positive, effective decision-making on managing and protecting key rivers and wetlands, ensuring wildlife and people can have access to safe fresh water for decades to come.

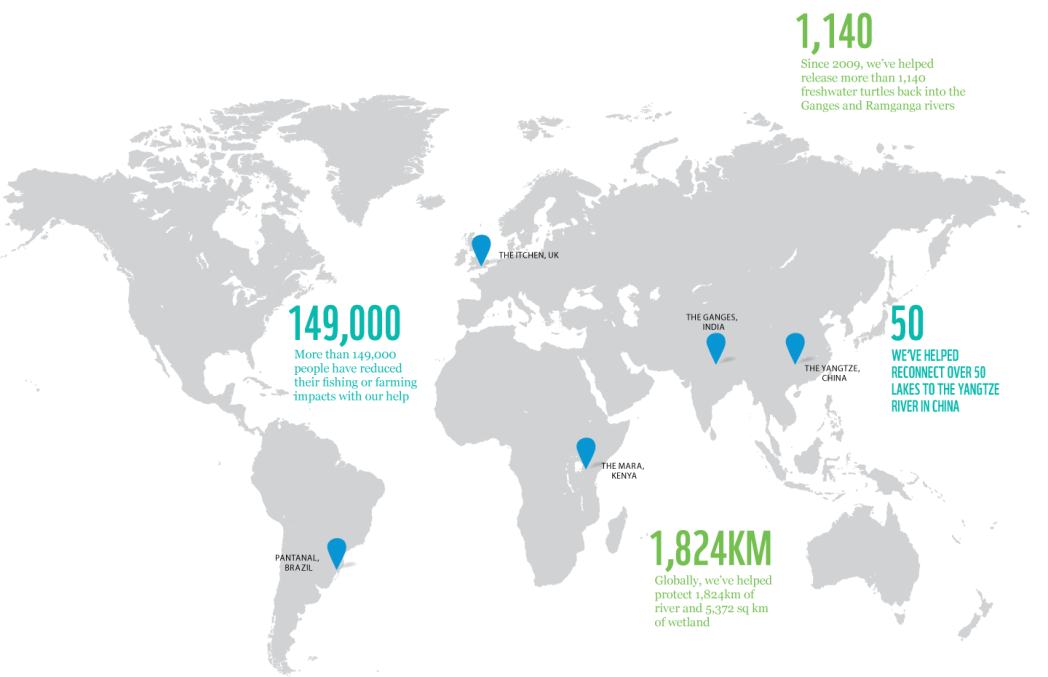

We know we can do this, and we're already achieving positive results. Read on to see examples of work we’re supporting along the Ganges, Yangtze and Mara rivers, Brazil’s Pantanal wetlands, and chalk streams here in the UK

Despite their value and importance, rivers, lakes and wetlands around the world are being severely damaged by human activity.

We’re acting wastefully, abstracting water faster than it can be replenished, and polluting and disrupting freshwater systems. Climate change is adding to the pressure, affecting fresh water and precipitation levels, and intensifying the threat of devastating floods and droughts.

Agriculture is a major concern

Globally, 70% of fresh water is withdrawn for agricultural irrigation, around 20% for industry and around 10% for domestic use. Converting natural grasslands or forests into farmland or plantations also affects the overall availability and cycle of water in a river basin.

Many rivers are polluted

Run-off from farmland and chemicals from industry impair water quality, kill fish and destroy ecosystems that wildlife depend on. In the Yangtze river, fish are dying due to pollution from agricultural run-off. Yet millions of people have little choice but to use these polluted rivers and streams for drinking, bathing and growing crops.

Dams are disrupting river flows

Dams and their supporting infrastructure disrupt free-flowing rivers, causing untold harm to freshwater ecosystems and wildlife. Fish migration routes are obstructed and breeding grounds reduced. Construction noise and increased boat traffic intensify the risk of harm to river dolphins and porpoises.

This challenge affects us all

Although we're used to having water on tap here in the UK, we can’t be complacent. Only 17% of England’s rivers are classed as healthy. Drained almost dry in places, and polluted in others, they’re under growing pressure from climate change. Yet research shows that a third of the water we take from rivers is wasted.

The need for fresh water bridges national boundaries, and links communities and wildlife across regions. Thanks to our amazing supporters, we’re working hard to help protect, restore and conserve freshwater resources on every populated continent.

Now, we want to use the knowledge, skills and experience we've gained to help safeguard rivers and wetlands, by informing and influencing governments and decision-makers on sustainable water use. These include river basin planning, efficient irrigation for crops, better planned dams, and governance of agriculture and industry.

Please help us safeguard fresh water, so people can prosper, and nature can thrive.

We’re empowering local communities to help protect the Ganges river and its incredible wildlife, including freshwater turtles and gharials.

Mr Luvkush farms along the banks of the River Ganges, near Hastinapur Wildlife Sanctuary. The sanctuary is home to an amazing array of wildlife, such as swamp deer, leopards, gharials, freshwater turtles, Ganges river dolphins and many species of birds and fish. But the rich biodiversity is under threat from over-abstraction, overfishing, sand extraction and pollution. Wetlands and marshes are shrinking, river flows are dwindling and wildlife is declining. By involving local people we’re helping to bring this mighty river back to life.

Community commitment

Freshwater turtles lay their eggs in the sandbanks that appear each year in the riverbed. Yet farmers like Mr Luvkush also use the sandbanks to grow watermelon and cucumber crops, exposing the nests to accidental damage. Now, the farmers act as protectors, monitoring the nests and notifying conservation teams, who retrieve the eggs and release the hatchlings into safer stretches of river. Since 2009, over a thousand turtles have been released into the Ganges and Ramganga rivers.

The Ramganga is a tributary of the Ganges and, in 2010, we helped start a Mitras initiative there. ‘Mitra’ means ‘friend’ in Hindi, and the Mitra members – all local volunteers, are true conservation champions. They carry out a wide range of activities, from measuring water quality and flow, to protecting wildlife. The Mitras also help carry out the annual Ganges river dolphin surveys. There are only around 3,500 of these dolphins left in the wild, so monitoring their numbers is crucial.

Dr Seema Mahendra is a Ramganga Mitra. As a child, Seema paddled in the river and played on its banks, and now she’s determined to help restore this once pristine river to its former glory. She often brings her mother and son to river conservation workshops: “It’s my responsibility to connect my children with nature, especially the river”.

We refer to the River Ganges as ‘Mother Ganga’ and worship her. If we revere her in action as we do in thought, we will be able to bring her back to her original, pristine state

Mr Luvkush

We’re tackling the impacts of sand extraction and overfishing, to give these rare porpoises the best chance of survival.

The Yangtze, Asia’s longest river, is home to 350 types of fish, 145 different amphibians, 166 reptiles, 762 bird species, 280 mammals and more than 14,000 different plants. Yet it’s also one of the world’s busiest and most polluted waterways. Today, there are as few as 1,000 Yangtze finless porpoises. They’re scattered in small, isolated groups in the middle and lower reaches of the main river and four of its lakes, including Dongting and Poyang. But their future is far from certain.

In Dongting and Poyang lakes, increased sand dredging for the construction industry has resulted in lower water levels, as well as a decline in water quality and flow to surrounding wetlands. This is affecting the number of fish that both people and the porpoises rely on. Overfishing is also reducing fish stocks and increasing the risk of the porpoises being accidentally caught in fishing gear, causing injury and possibly death. We’re working hard to address these threats.

Along the main river and in Dongting and Poyang lakes we’re helping to ensure that sand dredging is regulated to take the porpoises’ needs into account. In addition, we’re making sure that five oxbow lakes become ideal habitats for the short term translocation of some of them. We’re also increasing monitoring of the porpoises, and helping the government to undertake a five-year aquatic survey of the river.

To help fish stocks recover, we’re pushing for a year-round fishing ban, while at the same time ensuring local fisherman have alternative livelihoods in place. Plus, we’re helping to enhance law-enforcement activities against illegal fishing, in order to reduce the finless porpoise deaths it causes by 50%.

By 2025, we're aiming to ensure that illegal fishing is reduced by 80% and that sand dredging in porpoise habitats is fully controlled.

In the world’s largest natural wetland, we’re helping local farmers to restore and protect the vital water sources they rely on.

The Pantanal is an immense patchwork of lagoons, lakes and marshes, which supports a rich variety of valuable biodiversity, including magnificent jaguars. It also provides drinking water and supports essential services such as food production and tourism for the eight million or so people in the region. Small-scale farmer, José Apolinário (pictured above), is one of them.

José and his family live upstream, where the quality and quantity of water in the rivers and springs have a direct impact on the Pantanal below. Yet, increasingly, human activity is having a detrimental effect.

The Apolinários’ small property shares natural springs with a neighbour, and this has caused issues. “The water here didn't dry up, because it was protected by the surrounding vegetation,” explains José. “Then my neighbour cleared the vegetation and the water decreased quite a bit.” Thankfully, things have improved.

Thanks to the pact, the water has started to flow again. It’s really exciting to see

José Apolinário

In 2009, we began preserving the Pantanal’s headwaters. What started as a pilot project to restore natural springs through community planting has now become a large-scale plan for the future – the Pantanal Pact. It aims to guarantee water quality in almost 750km of rivers, as well as restoring degraded forest surrounding 30 springs and preserving further areas of riverside forest.

The pact brings together farmers with regional government, businesses and other communities. They take joint local action to restore, conserve and protect the Pantanal’s freshwater resources, and address social and economic issues concerned with water use. Through the pact, José got support and was able to work with his neighbour to safeguard their spring, fencing it off to prevent further damage by their cattle and restoring the vegetation around it.

In Kenya, we’re introducing water-friendly farming practices to boost crop yields, reduce erosion and improve the Mara river’s flow

The Mara river is the lifeblood of the whole Mara-Serengeti ecosystem. It supports millions of people and some of the most incredible wildlife on the planet, including rhinos, elephants and lions. Every year, hundreds of thousands of wildebeest, zebra and gazelle cross the river, in one of the world’s most spectacular wildlife migrations. But increasing demand for water to supply crops, livestock and industry is taking its toll.

As more land is cleared for farming, fertile topsoil washes into the river, clogging it with sediment and affecting the flow. By enabling local farmers to use simple yet effective conservation practices, we can help ensure the Mara provides enough clean water for everyone. Nancy Rono is an inspiring example of what this practical support can achieve.

Nancy, a single mother of three young boys, farms an acre of land on the steep slopes above a tributary of the Mara. In the past she struggled to keep the farm going because of a lack of clean water. “Before, the river was so dirty, all things were dumped there. This caused an outbreak of disease and people got very sick”.

Nancy now plants thirsty avocado and banana trees on high ground where they can absorb water, as well as strips of napier grass across the steep slopes. Its root systems stop soil and vital nutrients from being washed into the river when the rains come.

So far, we’ve helped more than 500 farmers like Nancy – and it’s made a big difference. The river here is cleaner and free flowing, and Nancy’s farm is thriving. She’s even built a shop to sell her fresh produce.

Now my farm is in good shape, and I can see the prospects are good. The income helps me to pay for the children’s school fees. They are going to have a good life

Nancy

Here in the UK, we're helping to improve water quality in five river basins, including iconic chalk streams like the River Itchen in Hampshire.

Some of our most beautiful rivers are chalk streams. Their pure, clear waters come from underground chalk aquifers and springs, flowing across flinty gravel beds. They make ideal habitats for otters, water voles, kingfishers, migrating salmon and many more wonderful wild creatures to thrive. But our rivers need help.

There are just 224 chalk streams in the world and most of them are in the southern half of England, with a few in northern France. Yet more than 77% are failing to meet required standards such as nutrient and oxygen levels, and only 12 are protected. We’re working with communities, farmers, industries and government agencies to address the issues.

The River Itchen currently supplies water to almost half a million homes. We’re working with local water companies and authorities to ensure abstraction is kept at a sustainable level. For example, we’ve been helping to promote the use of water meters, and encouraging people to save household water by making small yet effective changes. These include running washing machines and dishwashers on eco settings, and only when full.

We're also pushing the government to uphold its legal duties regarding fresh water. Last year, we took a case to the High Court to ensure the government uses all its powers – including rules and regulations – to protect our most precious rivers and wetlands, including Poole Harbour in Dorset, the River Mease in the Midlands, and the River Itchen.

As a result, the Environment Agency and Natural England must now set out plans that show how they will fully address pollution and, if needed, put in place enforceable controls to reduce the impact of farming and other activities that cause it. The first set of plans is due later this year, and we’ll ensure they are sufficient to meet the needs of the rivers and the court.

So far, we’ve improved seven kilometers of river and replenished 300 million litres of water, working across 2,000 acres of land across the UK.