An area equivalent to 88% of the UK’s land area was required overseas annually, between 2016 and 2018, to fulfil the country’s demand for just seven agricultural and forest commodities.

The risks associated with the production of these commodities continue to be high - meaning they could be fuelling the destruction of nature around the world.

In collaboration with RSPB, we are pleased to publish our highly anticipated report in full: ‘Riskier Business: the UK’s Overseas Land Footprint’.

Our report provides up-to-date data of the ‘Risky Business’ report, originally published in 2017, which highlighted the UK’s land footprint abroad associated with its imports of the 7 following agricultural and forest commodities: beef & leather, cocoa, palm oil, pulp & paper, rubber, soy and timber.

Key Findings

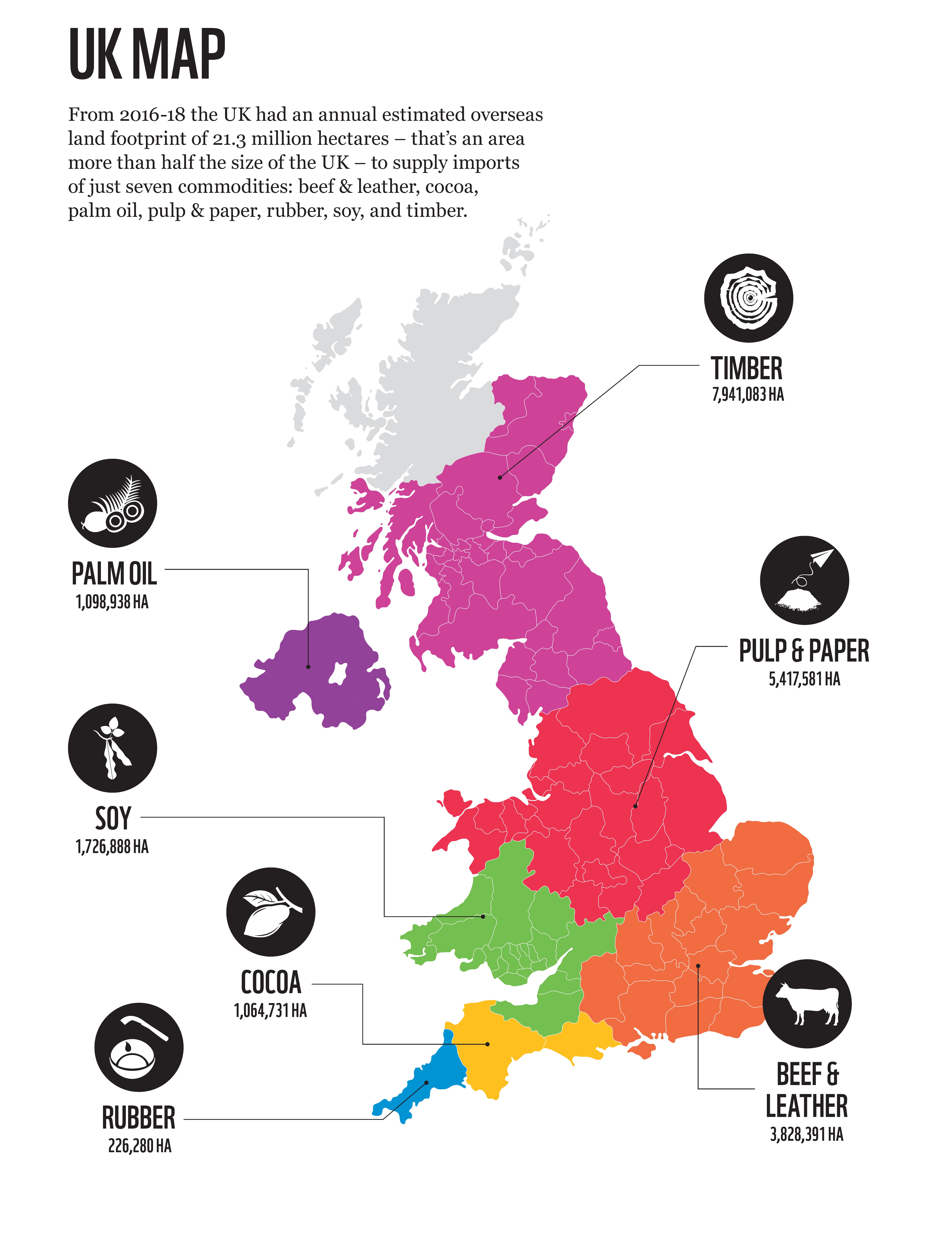

- A total of 21.3 million hectares (Mha) of land (88% of UK land area) were required overseas each year, between 2016 and 2018, to satisfy the UK’s demand for seven commodities (beef & leather, cocoa, palm oil, pulp & paper, rubber, soy and timber).

- On average 28 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) were emitted each year between 2011 and 2018, to produce only four of the commodities imported to the UK (e.g. cocoa, palm oil, rubber and soy).

- It is estimated that over 2,800 species, already under threat from extinction, could have been affected by the negative impacts associated with the production of these commodities.

- Around 28% (nearly 6 Mha or an area three times the size of Wales) of the UK’s overseas land footprint is located in countries assigned a ‘very high’ and ‘high’ risk score (i.e. those experiencing high destruction of nature and with poor track records of labour rights and governance).

The new report provides information of some progress made in the UK since the past report and provides new recommendations to governments, companies, financiers and citizens. See key asks below.

We call on the government to urgently

- Secure high environmental and social standards and safeguards in trade agreements, aligned with the UK’s commitments on climate, nature and people.

- Develop a post Covid-19 recovery package that ensures more sustainable and resilient supply chains.

- Establish a mandatory due diligence obligation on businesses and financial institutions.

- Implement an ambitious action plan in response to the GRI task force recommendations, going further than these where necessary to address the issues highlighted in Riskier Business.

- By the end of 2020, set a time-bound, legally binding target to reduce the UK’s overall environmental footprint by 2030, including a sub-target to halt deforestation and conversion from commodity supply chains by 2023.

- Lead the way towards global action to halt deforestation and the destruction of other natural habitats, both in international fora, such as the UNFCCC COP26, and through international cooperation with key producer countries.

We also call for action from:

Companies

- Set robust policies and time-bound commitments to halt deforestation and ecosystem

- conversion aligned with the Accountability Framework initiative, and implement these as soon as possible.

- Report publicly on progress towards policies and commitments.

- Engage with suppliers and support implementation of policies and commitments across your entire supply chain.

- Advocate for further action among peers and wider stakeholders (e.g. supporting calls for robust environmental and social standards in trade agreements).

Financial Institutions

- Set policies as well as pre-screening and monitoring systems.

- Report publicly on risks and impacts and on the progress in mitigating them; and request clients to do so.

- Enable the transition to sustainable commodity production (e.g. finance sustainable agriculture practices and nature-based solutions).

Citizens

- Purchase certified products whenever possible.

- Write to your local MP (or equivalent) to support policies and legislation for greener supply chains and further transparency and scrutiny over trade deals.

- Demand greater transparency and action from your supermarket and favourite brands

- Eat more sustainably (e.g. choosing plant-based products, eating less meat, wasting less food and, when possible, choosing locally sourced options).

What else does the report show?

The full report provides specific information on the risks to biodiversity, climate and human rights in three key highly biodiverse landscapes, associated with the UK’s trade in the following commodities: cocoa, palm oil and soy.

Cocoa from Ivory Coast

- The area of land used to produce cocoa in Ivory Coast increased by 50% between 2011 and 2018, from 2.7 Mha to 4 Mha. Over the same period, the country lost 2.4 Mha of tree cover, an area greater than the size of Wales.

- Cocoa production is concentrated in areas with the highest rates of deforestation, and there is evidence of forest clearance in certified cocoa cooperatives and within protected areas.

- Cocoa traders do not disclose which cooperatives they source from to supply the UK market. In the absence of greater supply chain transparency, it has to be assumed as a first order estimate that any cooperative within the country could be supplying cocoa linked to deforestation to the UK.

Palm oil from West Kalimantan

- Between 2011 and 2018, West Kalimantan province lost about 2 Mha of tree cover - equal to an area the size of Wales

- Major traders importing palm oil into the UK market (AAK, ADM, Bunge and Cargill) source from a large number of mills in West Kalimantan, very few (~10%) of which are certified by the RSPO

- Three UK banks - HSBC, Standard Chartered and Prudential - were identified as lending US$710 million to palm oil client companies in Indonesia. Of this, US$185million was lent to six companies owning mills in West Kalimantan; only one out of these 12 mills is RSPO certified

Soy from Mato Grosso

- Mato Grosso has the second highest rate of deforestation and land conversion of the major soy exporting states in Brazil, having lost around 2 Mha of tree cover between 2016 and 2018 - equal to an area the size of Wales

- Around half of all soy imported directly into the UK from Brazil comes from Mato Grosso – on average 298,000 tonnes per year between 2015-2017

- Between 2015 and 2017, Cargill was responsible for 87% of the total soy volume imported from Mato Grosso into the UK the market

Tanya Steele, Chief Executive at WWF, said:

“The hidden cost of the food we eat and the things we buy is all too often the destruction of nature overseas, threatening our climate and human health. Every hectare cleared brings us in closer contact with wild animals and risks a new global pandemic.

“We can only truly improve UK environmental standards if we stop importing food that causes deforestation elsewhere. As we begin the process of recovery from the pandemic, we urgently need a legal duty on companies to cut these activities out of their supply chains, and we can’t sign up to trade deals that have habitat destruction baked in. If we don’t take these measures, we are just starting the timer on the next global health crisis.”

Beccy Speight, Chief Executive at the RSPB, said:

“It is easy to feel distant from the destruction of forests thousands of miles away. But the global pandemic has thrown into sharp relief the fact that when we destroy nature, we gamble with human health.

“If we are serious about rebuilding a brighter future, we need new laws to ensure that companies can prove their supply chains are not putting us all at risk.

“The greatest crisis this country has faced since WW2 has physically cut us off from each other. For many, nature has become a link to the outside world and a source of solace. The links between thriving nature habitats and our mental wellbeing have never been more obvious. We cannot afford to underestimate the value of nature. Neither can we turn a blind eye to the power our choices, as a society, an economy and as individuals, have to change the world for the better.”

Nature and pandemics like COVID-19

Nature and pandemics like COVID-19

5 ways to stop deforestation in our food

5 ways to stop deforestation in our food