Why we protect wildlife

Animals and plants aren’t just valuable for their own sake – they’re also part of a wider natural environment that may provide food, shelter, water, and other functions, for other wildlife and people.

With so much wildlife at risk, the question people often ask us is how do we decide which animals and plants to focus our conservation efforts and funds on? Well, it’s not always an easy decision… but we do have criteria to guide us.

For example: 1) is it a species that’s a vital part of a food chain? Or 2) a species that helps demonstrate broader conservation needs? Or 3) is it an important cultural icon that will garner support for wildlife conservation as a whole? These are just some of the considerations.

"Our planet is so special and diverse there are still new species being discovered all the time. Meanwhile we’ve reported the terrifying news that vertebrate species populations have declined on average by over 50% since 1970. Whether your interest in wildlife is for its own intrinsic value or for its contribution to a functioning ecosystem that supports so many species as well as human livelihoods and well-being too, there is no denying that we, people, have an obligation to ensure we not only stop our damaging ways, but look to increase wildlife populations and strengthen the habitats they rely on."

Chief adviser for wildlife

Conservation in action

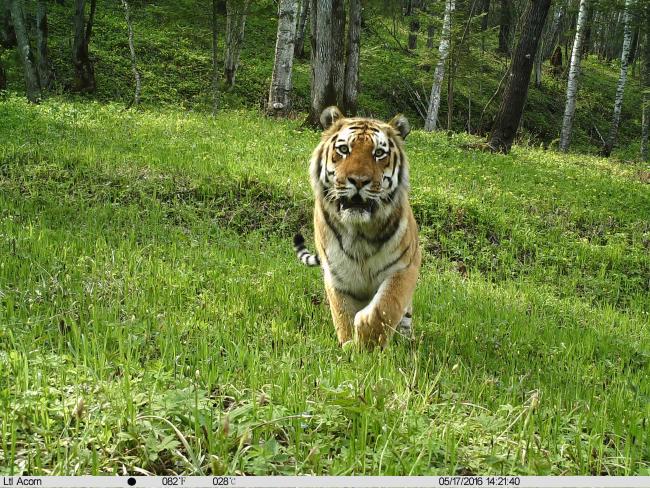

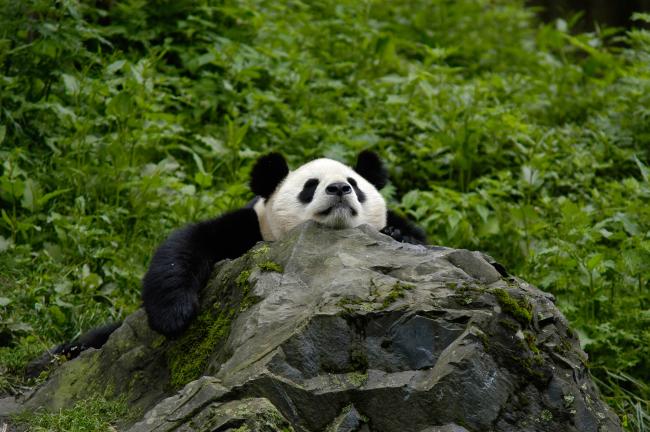

Over the past five decades, our field work has helped bring several iconic animals back from the brink of extinction – including white and greater one-horned rhinos, certain populations of African elephants, mountain gorillas, giant pandas and tigers.

We’ve also achieved important policy changes – for instance: helping bring about the global moratorium on commercial whaling; improving controls for trade in threatened species such as tigers; and regulating trade in over used trees, like mahogany, and fish such as sturgeons (caught for caviar).

Our work hasn’t just given a more certain future for specific wildlife, but has helped thousands more species by contributing to the conservation of all the diversity of life within their environments.

Our wildlife conservation efforts are also directly helping people, through improved livelihoods, food security, access to fresh water, incomes, and by strengthening communities, socially and politically.

The work we do is playing a part in at least five of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals, and contributing to poverty reduction in several parts of the world.

Global wild tiger numbers increase for first time in conservation history

Thanks to the collective efforts by governments and organisations, and the brilliant help of our passionate supporters and colleagues around the world, we were thrilled to see that wild tiger numbers have risen – for the first time in conservation history. Just over a century ago, there were thought to be around 100,000 wild tigers. In the past century, we lost nearly 95% of our wild tigers. By 2010 there were as few as 3,200 left in the wild (to put that in perspective, there are more tigers than this in captivity in the US alone). But due to enthusiastic and determined global efforts, and skilled conservation work on the ground in Asia, wild tiger numbers have now risen to an estimate of around 3,900. We’re stepping up our efforts to help wild tiger populations grow further – and you can help us.